Every so often something in Civil War history hits you like a punch in the gut. Whether it is a particularly visceral description of combat, or a moving letter from a soldiers’ loved one at home, the information in a source can affect you deeply; so deeply that it colors your perspective from that point onward.

I had an experience like this while researching my next book, The Guns of September: A Novel of McClellan’s Army in Maryland, 1862. Reading through a copy of the Richmond Dispatch from September 18, 1862, I came across the following passage: “Although official confirmation of the reported capture of the Federal garrison at Harper’s Ferry reached this city yesterday, no one doubts for a moment its reliability… The whole garrison, some eight thousand in number, surrendered on Sunday morning, besides which our forces captured about one thousand negroes.”

Captured one thousand negroes? Wait! Did I just read that?

Back I pored through my stack of books on the Maryland Campaign looking for some reference to the capture of contrabands by Stonewall Jackson’s men. Did I overlook it in James Murfin’s classic, The Gleam of Bayonets? Nope, not mentioned. Stephen Sears’s Landscape Turned Red? Not there. Surely it would be in Joseph Harsh’s Taken at the Flood. It wasn’t, and no sign of it in his Confederate companion volume, Sounding the Shallows, either. I searched without success through Ezra Carman’s history of the Maryland Campaign, Douglas Southall Freeman’s massive biography of Robert E. Lee, and G. F. R. Henderson’s biography of Stonewall Jackson until I finally located a brief mention of captured contrabands in D. Scott Hartwig’s voluminous To Antietam Creek. Then I found another more detailed treatment in a slim volume called Harpers Ferry Under Fire by Dennis Frye.

At last, I had found other researchers who noticed this sad historical episode. Frye’s account even cited the letters of a woman named Abba Goddard who witnessed Ambrose Powell Hill’s men scouring Harpers Ferry for black folks – men, women, and children alike. Hill’s men seized not only the military spoils of war, they also swept up any and all blacks they found in town after the Federal surrender, no matter where those people came from, or if they were freedmen or not. They even tried to seize free blacks serving on the staff of Captain William Trimble, a captured Federal officer.

I left this episode alone for a long time for a long time, even though it continued to nag at me like an itch I couldn’t scratch. Then Robert Wynstra’s At the Forefront of Lee’s Invasion called attention to the Army of Northern Virginia’s rounding-up of blacks in Pennsylvania during the Gettysburg Campaign in 1863 and immediately I recalled the events at Harpers Ferry in September 1862. No one had exposed that earlier incident in nearly as public a light as the events Wynstra recounted.

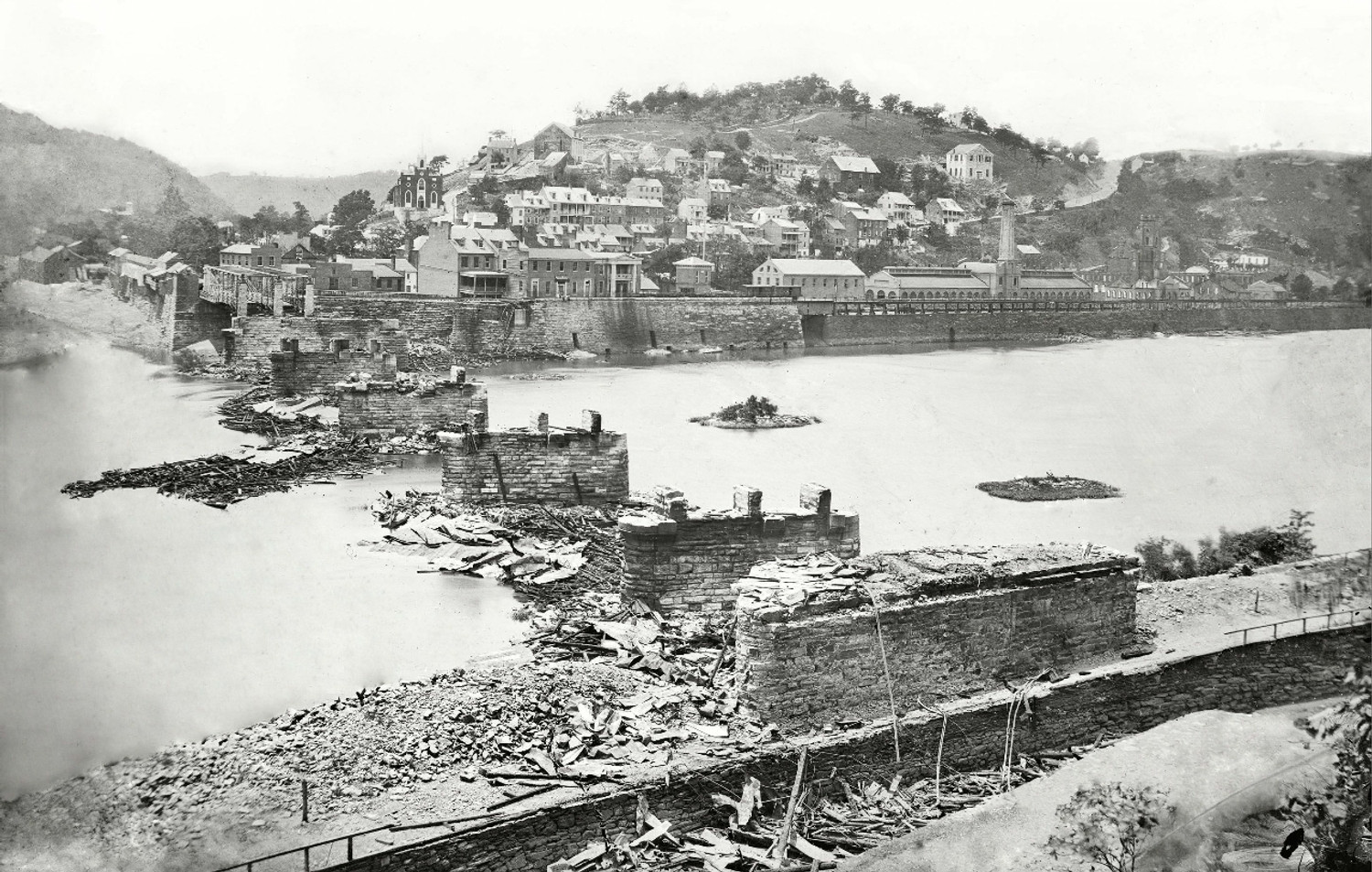

Until I read that entry in the Richmond Dispatch I had always studied the Confederate capture of Harpers Ferry in strictly military terms. It was one of Stonewall Jackson’s crowning achievements, a victory that forced the surrender of more Federal troops than at any time until the capitulation of 12,000 U.S. soldiers to Japanese forces in the Philippines at the outset of the Second World War. Yet here in A. P. Hill’s actions was evidence of something more than a battlefield triumph. Here was a disturbing example of chattel slavery in operation during wartime. Here I found the seizure and imprisonment by Confederate troops of human beings defined as mere objects, as property, as non-persons; a status that even the Federal term “contrabands” reinforced.

The story of Harpers Ferry’s contrabands told in the Dispatch, and augmented with a couple of details from Frye’s book, goes as follows. A. P. Hill detailed 1,000 or so men to collect and ship south the supplies captured at the Ferry. This included as many as 2,000 blacks, no small number of whom “belonged to citizens of Jefferson and adjoining counties … one gentleman from Clarke [County], who had lost 31 negroes, [and] found 28 of them in this lot.” Two train car loads of these people, “whom the Yankees had stolen,” claimed the Dispatch, then arrived in Richmond on September 23, “by the Central Railroad, direct from Harper’s Ferry. … Their masters propose to offer them for sale in Richmond, not deeming them desirable servants after having associated with the Yankees.” From here the contrabands sent to Richmond vanish from history, presumably auctioned off to distant locations in the Deep South.

Reflecting on this event made me uneasy, which is perhaps understandable given my past career studying German deportation operations involving human beings and rail cars during World War Two. That coincidence aside, reading about the events at Harpers Ferry forced me to realize that I had never considered seriously enough the meaning of the American Civil War for millions of enslaved people in the South. I had viewed their fate more as a distant intellectual notion generally separate from the war’s military operations, except on certain occasions like the incident at Ebenezer Creek when Sherman’s army left thousands of black refugees trailing his army to be captured by pursuing Rebel cavalry. Now, though, reading about rail cars of captured contrabands arriving in Richmond for the slave pens exposed the glaring hole in my thinking.

Don’t take me wrong here. I am in no way saying that the Harpers Ferry contraband round-up and Nazi depopulation actions are the same thing. They are not. Not by a long shot. I am also not pontificating on the American Civil War being caused by or fought for the eradication of slavery in the United States. That is an issue for others more versed in the sources to argue over. I also know for a fact that racism was widespread in Northern ranks and that the Army of the Potomac nearly revolted after Abraham Lincoln’s announcement of the preliminary proclamation of emancipation on September 22, 1862. Few Union troops or officers would claim in 1862 that their army was a liberating force bent on destroying slavery. They would argue that their twin purposes were to restore the Union and to put down rebellion.

I get it.

And yet despite these facts students of the war must recognize that the Confederate and Union armies operated in fundamentally different ways. The Harpers Ferry contraband incident illustrates this beyond a doubt. None of us anywhere would ever read that a Union army seized blacks upon capturing a location, searched the place for every last one of them, placed them in chains, and shipped them off to be sold in Philadelphia!

Here in the Richmond Dispatch I encountered a different situation altogether, a situation when ordinary Southern soldiers, men who undoubtedly considered themselves patriots doing their duty, acted as centurions enforcing the utterly despicable practice of enslaving innocent people just because the law and local custom defined them as less than human. What does one do with the fact that while devoted Southern men fought to protect their homeland from invasion, they were also defending an economic system that degraded both slaves and their owners? What does the blood sacrifice of Confederate troops during the war mean when their struggle for independence denied liberty, and even basic human dignity, to millions of people? Where is the glory in the pursuit of that objective?

These questions bother me to this day. I study and admire the fighting men of both the North and the South for persevering through the hardships they endured and yet when it comes to the cause for which Southern troops struggled, I can only shake my head. Defenders of Southern heritage might argue that one fight – the fight for Confederate independence – was not connected to slavery in the minds of most Southern soldiers. After all, the research seems to show that most ordinary Southern troops never owned slaves. This is a fair enough claim, I guess, but then how does one explain the actions of A. P. Hill’s men at Harpers Ferry? If those men were not enforcing the customs of Southern society at the time, customs that called for the rounding-up and re-enslavement of thousands of innocent people, some of whom were freedmen, what were they doing?

The only logical conclusion I’ve been able to reach is that fighting to secure Southern independence also meant fighting to defend slavery. The two things cannot be separated. Ordinary Southern troops in A. P. Hill’s command clearly seem to have understood this and they did their duty accordingly. It is we in the present who seem to have forgotten it and I can only wonder why on earth that is.